Above: Ellis Island in 1905.

United States of America

By Paolo Calvano

Migration to the Confederation started at the very beginnings of the history of this nation. Already from the end of the 18th century small groups of Italians that could be classified, in a very general sense, as merchants, artists and artillery men. In the middle of the 19th century with the failure of the insurrections in various European states, there was a consistent exodus of political refugees. Even in 1880 the migrants were only 44,000. From then on till 1900 the migrants, nearly all peasant farmers, and the majority from central and southern Italy, reached around 800,000. With the new century and an exodus of biblical proportions, that until the outbreak of the Great War, sees numberless young Italians disembarking at Ellis Island. There were three and a half millions of these “temporary” migrants (because half, in the same period, embarked for Italy) that arrived in the USA; nearly all males young and from the southern regions, with significant exceptions the minority of tradesmen from central and northern regions of Italy.

This temporary flow has some definite characteristics: young and very young, without women and children, largely from an agricultural background, gathered with fellow countrymen, and established themselves in areas already settled by Italians. These migrants have in mind one main aim to save in as short a time as possible, suffering privations, as much money as possible to use back in Italy. They are reluctant to learn the English language (they often do not know Italian as well) or think of naturalization or take to take up permanence in the USA. This great mass of workers is considered a workforce of a second order.

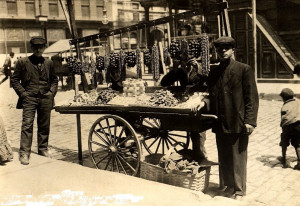

As unskilled workers they found work in the building industry, and construction of sewers, tunnels, railways and work in the wharves. Over half are employed as attendants or common workers. The dual condition illiteracy and not being specialist workers, made them vulnerable to exploitation, especially by other Italians to whom they turned to and who acted as mediators to help them integrate into the American community. Finding a job and a miserable lodging, resolving small problems of daily life, saving money like a bank or sending them back to the family in Italy. This also happened, for those that had the right to vote, to find themselves bartering with the local politicians for small personal favours. With the Great War and the big shortage of labour there was an improvement in the stability in the workplace and a rise in the quality of employment. Many Italians recycle themselves as wharf workers and become qualified miners in the coal mines. The smarter ones set up trade shops, restaurants, wholesale fruit and vegetable (wines and oil), they took risks as traders or in the fishing industry. In the meanwhile there began to spread, journalism being an accomplice, the stereotype of the mafia and the Italian organised underworld. “From the 1880s the Little Italies began to grow like mushrooms in the whole of America. Like a mosaic grouping based on villages or the regions of origin”.

In New York in 1920 lived 800,000 Italians, spread from Manhattan, Brooklyn, Richmond and Queens. There were also substantial settlements in Boston and Philadelphia (these were ports of call on the Atlantic), in Chicago, in New Orleans and at San Francisco. The preferred areas continue to be the states in the north east and the cities along railway lines or close to the mining industries where work was available close by.

Life in the Little Italies for individuals and families was based on some basic elements. The membership of the Society of Mutual Support, copied from the town of origin, and their ties with the Catholic Church, which was lived in a particular way and was different to the ways of the American and Irish Catholics. The Italians consider important the sacramental celebrations and the processions of their patron saints whereas they often set aside the obligation of Sunday mass, the financial support of the local church, obedience and discipline towards the hierarchy. The difficulties with settling in with fellow American religious followers are overcome slowly through the undertaking of the Scalabrinians Congregation and the Sisters of St Frances Cabrini (who undertook what today would be called migrant pastoral care) and also the attempt to bring Italian priests and create national parishes.

We must not forget that in many Italian communities and in some geographical areas there prevailed secular anticlerical ideas and in these areas the socialists and anarchists found their strongest followers.

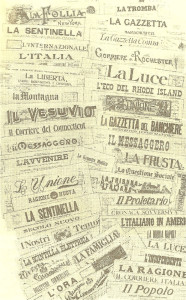

Very widespread were Italian newspapers. The first attempts in New York , as early as 1880 with Carlo Barsotti who founded the “Il Progresso Italo-Americano”, which carried on for over a century, and in 1894 “L’Eco d’Italia” of the follower of Mazzini G.P. Secchi of Casali. In the thirty years after 1900 there were about 30 dailies and a thousand “national” periodicals. In 1919 the total number of all publications was 800,000 copies printed. These periodicals carried out a strong national campaign in support of Italian culture and besides the religious and lay festival also exalt Columbus Day. Widespread also subversive publications tied to groups of anarchists, socialists and revolutionaries. The relationship with the official American trade unions are stormy and the Italians also in this field often personify anomalous figures in which extremism and the not always clear relationship with the masters, bankers and the mafia aren’t always representing the exception.

With the outbreak of the Great War and the involvement of the USA, the migratory flow decreased considerably (also because of the imposition of legislative restrictions) and the figure of the Italo-American was born, who is enlisted as a voluntary in the American army and find themselves fighting on the same side at the landlords. The war causes a crisis in the radical Italian groups, who after the 1919 strikes are marginalised or pass onto the ranks of the fascists or socialists. With the Fiume event and the assertion of the “mutilated victory” there begins a period of tension in the land of the USA where a xenophobic wave showed Mussolini as the saviour and defender of the menaced Italian values. In fact, in that period, “Il Progresso Italo-Americano”, under the direction of the proprietor Generoso Pope, an exponent of the Partito Democratico, took a pro fascist stance. Between the two wars there were about 600,000 Italian migrants on American soil, men but above all wives and children of migrants already established.

The crisis of 1929 and the depression that followed blocked migration and prompted returns to Italy. In 1930 there were still 1.8 million Italians, but in the following decade the Italo-American dream collapsed. At the end of the crisis for those that remained and suffered the economic crisis one can see more stability in the work place and betterment from a social point of view.

From 1940 onwards there matured the second generation of the migrants in whose minds there coexisted, and so contrasting, two worlds with antithetical choices, the rapport with the family which keeps them tied to traditions (but which is mostly an idea) and the external world, which urges them to a modern lifestyle which is attractive but superficial, without solid ideal references.

It is a marginal generation, in perennial conflict and with identity crisis. Interesting some of the figures that managed to emerge like the writer of Vastese origins Pietro Di Donato, the singer and actor Frank Sinatra and the sportsman Joe Di Maggio, just to give some examples, or personalities from the political world, or unions and organised crime, which grew because of prohibition.

With the declaration of the war by the USA (1941) the Italian in all effects became enemies and there were around 600,000 who were not naturalised. Naturalisation became the decisive step to accelerate the Americanisation process. The compatriots did their part, they purchase bonds to support the war and send their children to fight for their country. Notwithstanding this some thousands of Italians are interned, but only 210 are forced to enter the prisons that were set up. The service in the armed forces for the young ones and the use of the mature workers to substitute those that went to the front, allowed many of them to move away from Little Italy.

After 1945, with the end of the war and Europe under reconstruction, in the USA there arrived only one million migrants, because there was a privileged selection from northern Europe. In 1990 the Italo-Americans were numbered about 11 million, of whom only 10%, almost all elderly, were born in Italy. So the conditions for the greater number, those born and bred in the USA, entails a partial and minute recovery of their identity, tied in part to art and gastronomy, and at the “dusk of ethnicity” they represent the middle class, they are variously acculturated, they are white collar workers and are middle income earners. Hence they have finally become Americans from all points of view.

The Rail Disaster of Hansrote

On the 26 May 1913 near Hansrote, in West Virginia, a railway locomotive ran over a group of workers on the track. There were eleven victims and amongst these eight of them were Vastesi. We would like to remember these workers more than 100 years after their death:

Giuseppe Del Borrello (son of Sebastiano and Michela Napolitano) born in Vasto 17 November 1879 and married in Vasto 5 December 1901 to Elisabetta Celenza, daughter of Antonio. From the marriage there were five children, of whom Sebastiano died at the age of two in 1904. Giuseppe left his widowed wife and four children: Michele 9 years old; Concetta 5; Anna 3 and Sebastiano one.

Carmine La Verghetta (son of Francesco and Errica Suriani) was born in Vasto 13 March 1886 and married in Vasto 22 October 1910 with Teresa Raspa, daughter of Sebastiano. Carmine left his wife without children.

Luigi Di Spalatro (son of Nicola and Filomena Spadaccini) was born in Vasto 21 May 1872 and married in Vasto 5 December 1896 with Teresa Del Bonifro (daughter of Ferdinando). From their union there were born six children. Amongst these Maria Saveria who died in 1901 and Sante who died in 1904 both of them at the age of one year. Luigi left in Vasto his widow and four children: Serafina 16 years of age; Paolo 14; Nicola 11 and Sante 7.

Cesario Suriani (son of Giuseppe and Rosalia Roselli) was born in Vasto 2 December 1878 and married in Vasto 7 November 1908 with Teresa Roselli (daughter of Cesario). Cesario left his widowed wife and a two year old son Giuseppe.

Pietro Marchesani (son of Antonio and Maria Grazia Spinelli) was born in Vasto 6 November 1866 and married in Vasto 31 March 1889 with Rita Zappacosta (daughter of Vincenzo). Pietro left in Vasto his wife and five children: Antonio 23 years old, Vincenzo 19, Incoronata 16, Maria Michela 14 and Giuseppe 11.

Vincenzo Cicchini (son of Francesco) was born in Vasto in 1878. There are no records of a marriage. On the 30 November 1896 he applied for the passport. He left his parents in Vasto.

Vincenzo Cicchini (son of Domenico and Giovina Mattucci) was born in Vasto 20 June 1882 and no records of a marriage. The contacts with the railway company for the indemnity were dealt with directly by his father Domenico who was living in the USA.

Giuseppe Cicchini (son of Luigi and Eugenia Stivaletta) was born in Vasto 22 January 1890 and there are no marriage records. The beneficiary of the indemnity was his under age sister Annunziata, who was helped by her brother Vincenzo and grandfather Giuseppe (son of Francesco).