This documentary is based on interviews of Vastesi migrants mostly in Perth and some in Vasto. It concerns Vastesi migration and focuses on Australia. It runs for 1 hour 18 minutes.

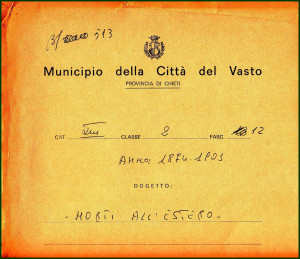

There are some details and documents of Vastesi migration for each of the continents of this world of ours. Select from the menu.

Vastesi Migration to Australia

This paper is based on the above documentary. It was delivered at the Royal West Australian Historical Society in 2013.

Vastesi_Migration_RWAHS

Italian Migration in the world

The ships depart for distant lands, suitcases full of dreams and nostalgia

By Beniamino Fiore

Since the years after national unification migration to foreign lands represent an important phenomenon tied to the changing demographic, economic & social events of the kingdom. The phenomenon was caused by the survival of the individuals and the families, which became a problem from the drastic reduction in employment opportunities due to the disequilibrium between the demographic growth and the economic development.

In the last decades of the 19th century Italy finds itself still in the first phase of the demographic transition process: that of declining mortality rates and a continuation of the birth rate, with the consequent natural increase in the population. At the same time changes in the productive structures and in particular the changes of the technologies in the agricultural and industrial sectors created a disequilibrium in the productive sectors, social classes and territorial areas, which caused the disappearance of old professions and an excess of labourers.

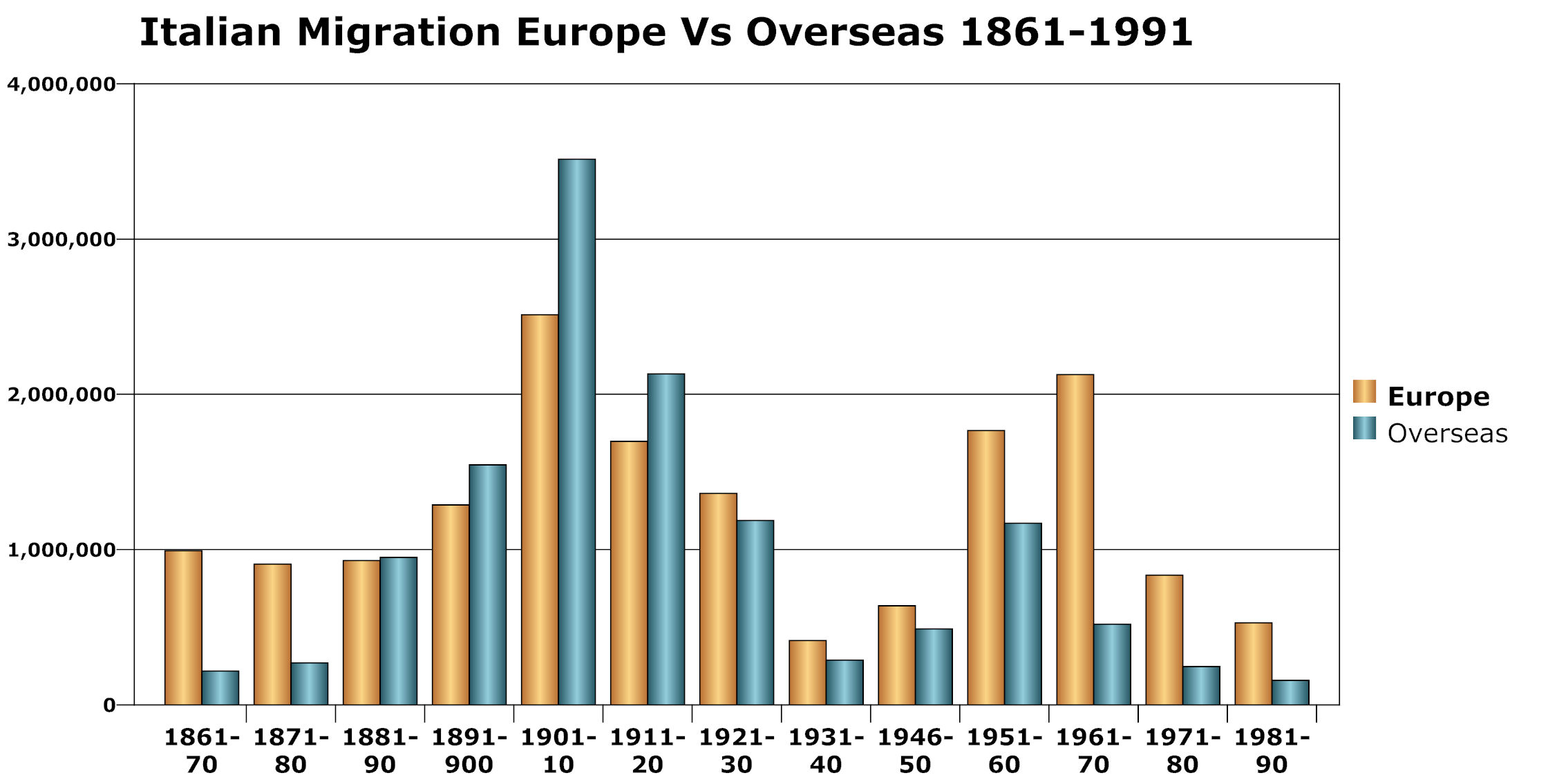

The numbers involved were very substantial. The estimates between 1876, when the statistics were begun officially, and 1976 over 24 million people left our national territory. Within this long period there were obviously significant variations. The period when it reached a maximum was between the last decades of the 19th century and the WW I (with almost 14 million departures).

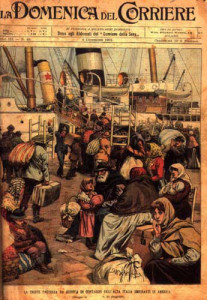

Those painful voyages on the oceans

And for a bed “a dog’s kennel”

Teodorico Rosati, health inspector, description of one of the many voyages of the period: “Crouched on the blanket, next to the steps, with the plates between their feet, our migrants ate their meals like the paupers at the doorways of the convents. It’s a humiliation from a moral point of view and a danger to their health, because as anyone can imagine what it meant to be in a boat tossed about by the waves into which was thrown all the available and involuntary rubbish of those travelling people.

The crossing in such conditions, was a true adventure that lasted from 25 to 30 days, sometimes less, and it depended on those ships of Lazarus as these “sea carts” were called, where one lived in unbelievable inhuman crowding, with drowning a part of the day. The cost of the voyage was substantial. An investigation undertaken by Agostino Bertani in 1892, part of the Jacini agricultural enquiry on the conditions of the peasants, revealed that a one of them in Basilicata, with a hard days work only earned up to one lira, declared that he had to pay 235 lire to the agent to organise the migration voyage.

The voyage, especially in the first years of migration, was for many of them a very hard experience, if not an altogether traumatizing experience for some. Amongst some the sad episodes of those years besides the many drownings we limit ourselves to point out the 18 dead on the Matteo Bruzzo ship due to lack of food in 1888, and the following year the 27 migrants who died of suffocation on the ship Frisca. “Those painful voyages on the oceans” as they were called by the Domenica del Corriere…

According to Teodorico Rosati “the migrant lays down fully clothed on the bed, he places all his bundles and suitcases, the children leave their urine and excretement, and most of them vomit”. After a few days every bed becomes “a dog’s kennel”. (Source: www.rivisondoliantiqua.it)

Concerning the destination of the migration movements, between 1876 and 1885 the main destination was central Europe (around 64% of the total migrants). The main countries were France, Switzerland, and to a lesser degree Austria-Hungary and Germany. From 1885 until 1920 a greater number went overseas, above all to Argentina, Brazil and the USA.

The emigration was not an even distribution from all over Italy, rather over time there were variations from different areas and various numbers. From a timing point of view it was from the regions of northern Italy that showed the greatest interest in migration.

Towards the end of the 19th century, by now it had become a mass migration, were influenced by two factors: the creation of a new demand for labourers from the Americas, which was the pulling factor, and the revolution in maritime transport due to the introduction of steamships, which brought about a substantial reduction in time and cost of the voyages.

On the 26th January 1902 the weekly “La Domenica Del Corriere” published some correspondence from the capital of Argentina which described the fate of many Italians who landed in that distant place. One reads, amongst other things: “Every ship that arrives in Buenos Aires unloads onto the wharves of Port Madeiro thousands of Italians, almost all peasants hallucinated by the mirage of America who do not know where it is nor what it is.

Migrants, be on your guard!

It is necessary to put migrants on their guard against the abuses which they can be victims of persons that have little honesty, which are often met at the point of disembarkation, offering the migrants to find them work, to change money or to take them to their relatives or friends. To help migrants from these harassments that often attend them when they arrive at their destination, a number of charitable associations have been formed. A number of these associations have been formed in New York and other ports of America.

Its worthwhile to avoid these obstacles that these associations have the duty to look over and so make use of their service, even though in general the migrants are loath to make use of. They are the following: The Society for the Protection of Italian Migrants, The Italian Institute of Welfare and The Society of San Raffaele. The first of these societies exercises the welfare of the migrants from their arrival in Ellis Island, where they are taken to be examined and allowed to land. The second helps the migrants who have been allowed to land, and stay in New York for a few days. The last association looks after the welfare o9f women and children.

(Istonio: 30 August 1903)

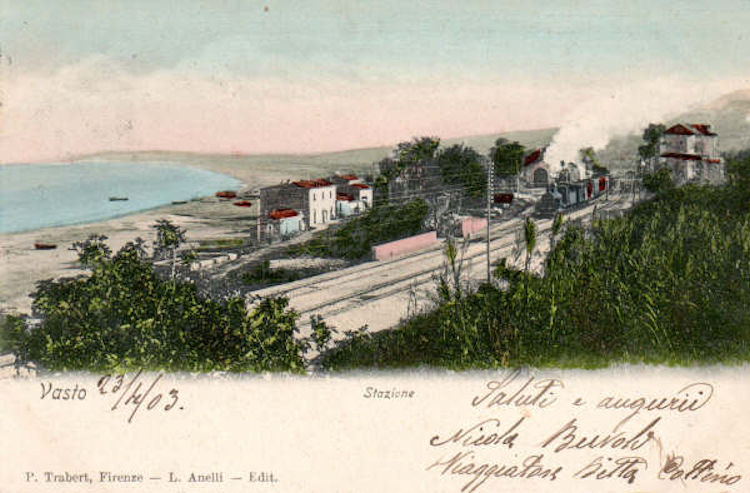

Vasto railway station early 1903

America for them is a lottery: they play putting their life at stake! The number of new arrivals is published next to the ship’s load, as though it was about import goods.”

What happens after the disembarkation? There is more on “La Domenica”: “As soon as foot is set on the soil, the poor travellers go to the so called “”Hotel de Immigrantes” which rises on a muddy strip of land between the turbid Rio de la Plata and the city. The hotel is packed. The work of spreading all these people in the whole country happens very quickly. Next to the refuge for the migrants there is “Oficina de Trabajo” which receives requests for workers and distributes the jobs; the migrants with families are taken on site at the expenses of the state”.

It seems a very good thing, but, the correspondent of “La Domenica” points out: “Theoretically the organisation is good, but its function is often inhuman. The jobs for which labourers are needed often are only temporary; when its finished the workers are sacked; these miserable people are left without resources in the middle of an unknown country, alone, unheard and ignored. And they cannot go back; the migrant can travel free on all the lines of the republic, but only in one direction, always forward, towards the outskirts.

Argentina needs to decentralise the population. The law is wise, but pitiless. Arriving inland the hopeful migrants are practically prisoners in the country”.

Between 1901 and 1902 the big flood of our migrants begin to move towards the United States.

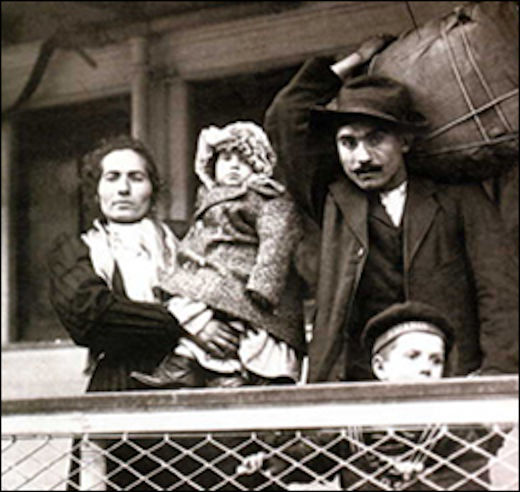

The race to embark becomes breathless. There are those that sell, those that make debt, even those that rob, to keep happy the exorbitant demands of the wheelers and dealers (illegal for fifteen years, but still in existence) that beat the countryside to engage migrants: thirty dollars, and then departure. The law number 23 of 31st January 1901 tried to regulate the flow and created a Commissioner General of emigration. But there is need of other things. Hunger is hunger, and by all means, in all manners people flock the wharves to compete for the right to find bread in some other part of the world. Eighty eight percent of those leaving is made up of men (from 14 to 45 years of age), only twelve percent females. These are figures that show the desperation of migration.

Ellis Island – “The island of hope” and also “The island of despair”

The slave drivers of the shipping companies make golden deal. They stack men like stock, up to the bridges and the holds, a full boatload can bring sixty thousand dollars, ands after three weeks or a month they let the dumbfounded human flocks onto the wharves along the Hudson River. The worst was yet to come. Big barges loaded the men again, ferried them across the bay, and unloaded them on Ellis Island. On this big rock was erected the anti chamber of the USA. The emigrants are divided in groups of thirty, to each one a small card was given with a name, a letter and a number. Here begins the long wait, made of fear, of hope, of anxieties. In long columns, the men are made to file past two wings of doctors. From a summary visit could depend the destiny of a life. The health officer have a chalk in their hand, often someone writes some signs on the men’s clothing. Mysterious signs, that only a few, in that great mass, for the most part illiterate and no English whatsoever, manage to interpret: CT stands for trachoma, H for heart, G for goitre, PG for pregnant. If the diagnosis was confirmed, very often the bitter compulsory repatriation followed. Statistics say that around 15% of the migrants were affected by some disease.

With $17 in their pocket (the average value attributed to each migrant) 170,000 Italians leave for the conquest of America. It’s a miserable beginning. The “little bosses” are waiting in ambush, for a mouthful of bread they engage for themselves the newcomers and make them work in desperate conditions, assuring them a miserable abode and just enough food to survive. And yet, despite this introduction, many manage to save money: 300 million lire flow annually to Italy. The history of our migration to the United States, from the beginning of last century, cannot forget all this. One can understand then the tendency of the Italians to flock to the ghettos, their solidarity as poor people (that sometimes lead to a criminal mafia conspiracy), and above all the inextinguishable nostalgia of a generation who could not adapt to this new country.

Mamma mia dammi cento lire

Con queste parole, una nota canzonetta popolare esprimeva le speranze e i drammi di chi cercava nell’emi-grazione verso le Americhe una via di emancipazione economica e sociale.

Mamma mia dammi 100 lire

che in America voglio andar!

Cento lire io te le do

ma in America no, no, no!

I suoi fratelli alla finestra:

Mamma mia lassela andar!

Vai, vai pure o figlia ingrata

che qualcosa succederà!

Quando furono in mezzo al mare,

il bastimento si sprofondò!

Pescatore che peschi i pesci,

la mia figlia vai tu a pescar!

Il mio sangue è rosso e fino,

i pesci del mare lo beveran!

La mia carne è bianca e pura,

la balena la mangerà!

Il consiglio della mia mamma

l’era tutta la verità,

mentre quello dei miei fratelli

resta quello che m’ha ingannà!

Dear Mother Give Me 100 Lire

With these words, a well known popular song, expresses the hopes and tragedy of those that tried to find in migrating to the Americas economic & social emancipation.

Dear mother give me 100 lire

as I would like to go to America

A hundred lire I will give you

but in America no, no, no!

His brothers at the window:

Dear mother let her go!

Go, go if you will ungrateful daughter

but something will happen!

When they were in mid sea,

the ship sank!

Fisherman that catches fish,

go and fish for my daughter!

My blood is red and fine,

the fish of the sea will drink it!

My flesh is white and pure,

the whale will eat it!

The advice of my mother

was all very truthful,

while that of my brothers

was that which deceived me

In the years following the first world war conflict emigration resumes intensively, with increased numbers involved, but it’s a short lived phenomenon. From the second half of the 1920s in fact, migration diminishes progressively due to the restrictions imposed by the United States and the p[policies of the Fascist government. The regime obstructed migration to build up a greater population, for the purpose of keeping workers wages low and have many youth for the army.

The migration flow takes up again after the Second World War, with a consistent strength until the middle of the 1960s. In these decades the departures are divided almost equally between the nations of Europe and overseas, (Australia in particular) and after to orient itself towards the industrialised countries of Western Europe: Germany, Belgium, and Switzerland, who showed a strong need for foreign workers.

This flow also continues in the 1970s but with a tendency of a constant decline. In the succeeding decade the returns are higher than the exits and so emigration, at least in numbers is by now overcome.

However, in the last decade or so there is a renewed flow, of young people in particular, to seek work overseas as Italy faces economic problems and a large percentage of youth are unemployed.